BRITISH RAIL’S “FLYING SAUCER”

The next flying saucer arriving at Platform 4 is the 1048 Cross Country service to Edinburgh, stopping at Morpeth, Alnmouth, Berwick-upon-Tweed and Dunbar…

UNTIL THE ELECTRIFICATION of mainline rail lines in the 1970s and 1980, British train passengers travelling from the late 1960s had the dubious pleasure of being pulled around the network by a variety of diesel locomotive classes, with some displaying dubious reliability – although fondly remembered nowadays by rail enthusiasts. However, I suspect that these train spotters – and all but a handful of those who are interested in UAP/UFOs – will be completely oblivious to the fact that British Rail, the state-owned company that owned most of the country’s rail network and rolling stock, submitted a design for a flying saucer in the 1970s. Yes, you heard that right. A flying saucer.

It's not every day that a train company submits a proposal for a flying saucer – but British Rail certainly did in the early 1970s.Of course, British Rail itself wasn’t exactly interested in constructing a flying saucer back in the early 1970s – the organisation had enough on its plate in terms of dealing with labour disputes, ancient working practices and improving on the buffet car offering of cheese sandwiches with their legendary curled up ends. Charles Osmond Frederick, an engineer specialising in the interaction of rails and wheels who worked at BR’s technical centre in Derby, was responsible for the flying saucer proposal.

Application number GB13120990 was filed by Jensen & Son on behalf of BR on 11th December 1970 but referred to a “lifting platform” rather than a flying saucer. Perhaps this description was chosen by Frederick or the Board so that the Patent Office wouldn’t dismiss his idea straight out of hand.

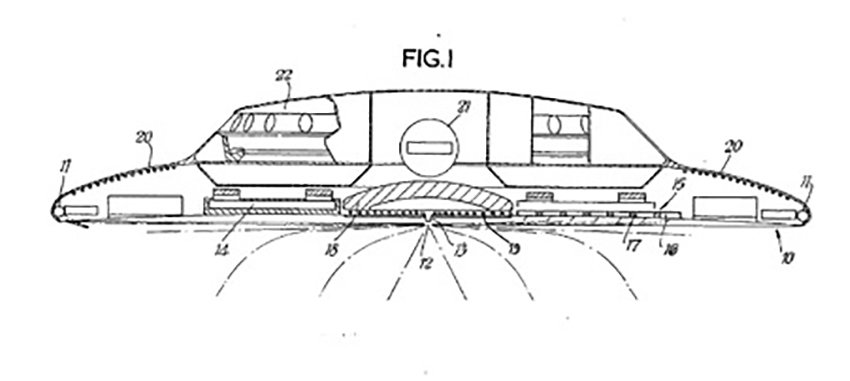

By March 1972 the original design had been amended and re-registered by the British Railways Board. Charles Osmond Frederick clearly did not believe in small, incremental technological progress. His design had developed beyond a mere “lifting platform” to a large passenger craft intended for interplanetary voyages. It was to be powered by a “controlled thermonuclear fusion reaction”, the reaction itself being “ignited by one or more pulsed laser beams”. The pulses would be generated at a rate of over 1000 Hz in order to prevent resonance building up, something that if left unchecked could have damaged the craft. These pulses of energy would have been emitted through a nozzle into a series of radial electrodes that ran along the underbelly of the vehicle. This generated electricity that passed through a ring of powerful electromagnets, or superconductors if available, accelerating subatomic particles that would provide both lift and thrust.

To protect passengers and crew inhabiting the upper section of the craft, a thick layer of metal would have acted as radiation shielding. A section of the original application is listed here (with the numbers signifying notes on the drawing removed):

“1310990 Space vehicles BRITISH RAILWAYS BOARD 10 March 1972 [11 Dec 1970] 59083/70 Heading B7W [Also in Division G6] A space vehicle includes a platform under which is provided a thermonuclear fusion zone to which liquid fuel is supplied under pressure to be ignited by beams from lasers. The platform mounts electromagnets, possibly superconducting magnets, to deflect charged particles produced by the fusion reaction; some particles are deflected so as to be received on insulated electrodes for generation of electric power. Excess thermal energy produced in the reaction is removed by cooling tubes to a radiating surface. The lasers may be energized by a homopolar generator. The latter may also be used as a reference for stabilizing the vehicle by varying the electrostatic voltages on sections and also the fields from magnets, the thrust on the vehicle can be directed to control the attitude and direction of the craft. A passenger cabin is included.”

A patent was granted on 21st March 1973. Part of the documentation reads as follows:

“The present invention relates to a space vehicle. More particularly it relates to a power supply for a space vehicle which offers a source of sustained thrust for the loss of a very small mass of fuel. Thus it would enable very high velocities to be attained in a space vehicle and in fact the prolonged acceleration of the vehicle may in some circumstances be used to simulate gravity.”

Whilst the Patent Office were clearly happy enough to grant a patent for Frederick’s invention, in order to realise it, a lot more work would have needed to be done – and his ideas for nuclear fission entailed orders of technological development way beyond what was possible in the 1970s.

However, British Rail – or maybe even Frederick himself – was unable or unwilling to stump up further money for this original patent when it finally came to renewal in 1976. It was allowed to lapse and the organisation’s flying saucer would have remained hidden history but for the efforts of a keen-eyed patent-spotter in the mid-2000s.

When the patent for Frederick’s flying saucer was unearthed in 2006, the British media – always ready to poke fun at the trials and tribulations of the country’s rail network – had something of a field day with the story. The above article appeared in the Daily Express.

In 2006, David Wardell, editor of Inventor’s World magazine, discovered the British Railways Board design at the Patent Office in Newport, South Wales. He was rather surprised that the organisation had submitted the idea in the first place:

“It seems extraordinary that the British Railways Board should have patented a spaceship. The plans were developed and amended over a number of years so they must have though there was something in it. You don’t go to all the expense of issuing a patent for a prank. We know now that anybody who flew in this spaceship would have been killed. They’d have been exposed to very nasty nuclear irradiation.”

Back in 1970, Charles Osmond Frederick did not have to twist any arms for the British Railways Board to file his original patent application. It was confirmed in 2006 that BR employees who came up with inventions had to patent them to ensure they did not personally profit from any work done during office hours. This was in the designer’s contract of employment, so Frederick was legally bound to comply. A spokesman put the whole matter to rest with a final, simple statement:

“British Rail never had any interest in space travel.”